|

Something Has Passed From the Game By Gerald Eskenazi |

|

|

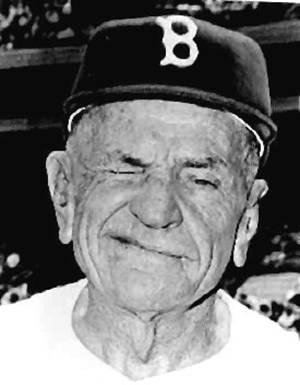

"The Old Professor,"

Casey Stengel. |

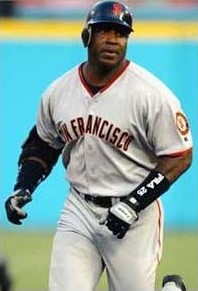

Roger Clemens, losing his lustre.

Barry Bonds, anti-hero. |

|

By Gerald Eskenazi Long before A-Rod made

$!6,000 an inning, and Roger Clemens didn’t take steroids (but his wife did,

prepping for a Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue), we loved our athletes. And

I’m not talking about the affection from the guy in the street—I’m including

my colleagues, the sportswriters. Why, even Congress loved

sports—as did the Supreme Court. The wise men ruled in 1922 that baseball was

exempt from anti-trust laws because it was a local, not interstate, endeavor. But 50 years ago,

Senator Estes Kefauver summoned Casey Stengel, and his fabled switch-hitter,

Mickey Mantle, to a hearing on the game. This is an edited exchange

among the courtly Senator, the befuddling, and syntax-challenged Stengel, and

Mantle, the Oklahoma farm boy: Kefauver: “Why is it

baseball wants this bill passed?” Stengel: “I would have to say at

the present time, I think that baseball has advanced in this respect for the

player help. That is an amazing statement for me to make, because you can

retire with an annuity at fifty and what organization in America allows you

to retire at fifty and receive money. I would say the reason the owners would

want it passed is to keep baseball going as the highest paid ball sport that

has gone into baseball and from the baseball angle, I am not going to speak

of any other sport. I am not here to argue about other sports, I am in the

baseball business. It has been run cleaner than any business that was ever

put out in the one-hundred years at the present time. I am not speaking about

television or I am not speaking about income that comes into the ball parks:

You have to take that off. I don't know too much about it. I say the

ballplayers have a better advancement at the present time.” Kefauver: “Mr. Mantle, do you have any observations

with reference to the applicability of the antitrust laws to baseball?” Mantle:

“My views

are about the same as Casey's.” Laughter from the Senators and the gallery. Contrast that with the confrontational tone that marked baseball’s

recent hearings over steroid use—indeed, it seemed to devolve into party

lines, with the Republicans backing the highly paid Clemens and the Democrats

in the corner of the working stiff who used to inject him. Not too long

before that, Congress took a look into that “wardrobe malfunction” in the

Super Bowl broadcast that now, just a few years later, seems so naïve and

unimportant. Our love affair with our athletes had never been problematic until

Nixon came along. Everything the public knew of our sports heroes came from

us, the journalists. Consider the source. There was a funny, quirky columnist

for The New York Post, when I was just starting out in the Sixties, named

Jerry Mitchell. After the obligatory few drinks at a post-game bar, Mitch

would tell us about his baseball travels—such as the time he actually roomed

in a sleeper car with Satchel Paige. That came about because Mitchell was

traveling with the Giants and Indians, who were barnstorming through the

Southwest in spring training. Paige was on the Indians. One night (I’m sure it was late), Mitch came back to his bunk—the

train was on a siding for the night. As he opened the door, he heard an

agitated Paige call out, “Who’s that?” When Mitchell told the famed pitcher,

Paige replied, “Get out—my wife’s visiting me!” “I found out he had a ‘wife’ in every town,” Mitchell chortled in

retelling the story. So we were pretty close to the subjects we were writing about.

Actually, so were the political writers. Then came Watergate, and Nixon

and…well, all of us in the business know the rest. Politicians became fair

game, as did every public figure—including our one-time heroes, the great

athletes. Now, one agent tells me, “I spend more time on paternity suits than on

contracts.” And the National Basketball Association has to deal with the fact that

one-fourth of its drafted players has been through the criminal-justice

system. Our heroes see their names in the papers these days for everything

from being at the scenes of drive-by shootings, to brawls in strip clubs, to

spousal abuse. The Internet, and You Tube makes it impossible to hide—even if

reporters these days were inclined to overlook the feet of clay of many of

the athletes they write about. It used to be so easy being a baseball fan. Back in Brooklyn—yeah, we

used to have a ball team there—we spent those muggy summer nights at the

candy store arguing over statistics, numbers that take on an importance in baseball

that rival mathematicians who understand e=mc2. But first it was Barry Bonds who tortured us as he approached

“755”—Hank Aaron’s record number of career home runs. For him, for Clemens,

for all those other ‘roids who tampered with our fixation with fixed numbers,

there has been a melancholia among sports fans everywhere. For when you take away a cherished number from baseball fans, you tear

away a part of what they love. In no other sport are statistics as much a part of the game as the

game itself. Archimedes himself never got a measurement as elegant as 60 feet

6 inches between pitcher and batter. Many of the great numbers already have

been surpassed, but we accepted them, albeit grudgingly. Gone, forever, is

“60,” Babe Ruth’s single-season home run number. Strewn among the winds of

history is “2,130,” the number of consecutive games played by Lou Gehrig. The

persnickety Ty Cobb lost his “96,” his single-season stolen-base record.

Perhaps the only magic number left is “56,” the number of consecutive games

in which Joe DiMaggio hit safely. Baseball—with its season’s preparation beginning in the winter, then

stretching 162 games over the spring, summer, and fall—fills our heads with

numbers. There are assists, there are putouts, there are balls, there are

strikes, there are sacrifice flies, intentional walks, innings pitched,

on-base average, slugging percentage, caught stealing. In recent years baseball intellectuals have created such

arcane definitions as “quality starts.” You get the picture. But with all

these, some stick out more than others. The great numbers are often what

decide arguments over who is the greatest. You can’t argue with numbers. As

Stengel the one-time Glendale, Calif., banker, used to say, “You could look

it up.” Something is gone from the game. Maybe it’s our innocence. Yet, my confession as a voter for the Baseball Hall of Fame: I

will--unhappily--vote for Bonds, the anti-hero, and Clemens, the pathetic

liar. For even before the suspicions took root, they were extraordinary

players. Hard to imagine, but many of my sportswriting predecessors never

voted for Ted Williams as their top choice because, quite simply, they didn't

like him. (Twenty of the 302 voters left him off the ballot!) Would we feel differently about Barry and Roger if the steroids thing

hadn't come up? As Hemingway, a DiMaggio fan, has Jake Barnes conclude in

"The Sun Also Rises": "Isn't it pretty to think so?" |

|