|

50 Years from that Fateful Day in By Martin J.

Steadman |

||||

|

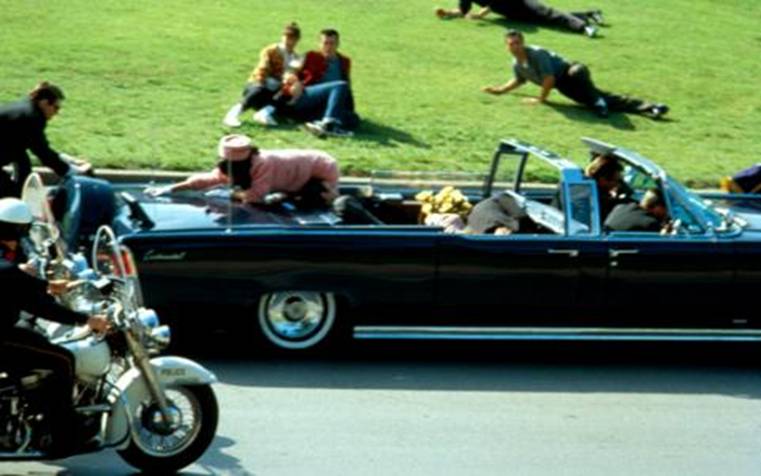

Zapruder Film |

||||

|

Fifty Years from that Fateful

Day in By

Martin J. Steadman The

murder of President John F. Kennedy in As

early as November 25, on the day the President was buried, Federal Bureau of

Investigation Director J. Edgar Hoover and newly-sworn President Lyndon

Johnson reached agreement to squelch widespread speculation that Lee Harvey

Oswald had acted in concert with conspirators unknown. And

of all the mysteries about the assassination that linger 50 years later, none

is more baffling than the decision by Attorney General Robert Kennedy to

distance himself and his Justice Department from the feeble inquiry that

followed. The Johnson/Hoover deal to stifle

speculation about the assassination of President Kennedy resulted in the

appointment of a Presidential Commission to inquire into everything that

happened on that weekend in That’s right. The new President and the FBI Director made

up their minds immediately that Oswald killed Kennedy, and Ruby killed

Oswald, and case closed. The

White House moved swiftly. Within days

President Johnson lined up the members of his Blue Ribbon panel, and on

November 29 he signed an Executive Order creating the President’s Commission

on the Assassination of President Kennedy.

Within seven days of the death of John Kennedy and five days of the

murder of Lee Oswald, the White House had assembled an impressive group of

national leaders headlined by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Earl

Warren. The panel was charged with

“finding the full facts of the case and reporting them, along with

appropriate recommendations, to the American people.” Shortly

after the announcement of the appointment of the Warren Commission the

Associated Press sent a story on its national wire, reporting that a

high-ranking official of the Justice Department said the murder of President

Kennedy was the work of a lone assassin, and no evidence of a conspiracy had

been found linking Oswald to Jack Ruby or anyone else. The Associated Press at that time had my

respect and admiration. But that was

the moment my illusions were forever shattered. The AP was used and abused by the President

and the Director of the FBI. I

was in Already the newspaper stories out of The Herald Tribune editors sent Haddad to No one at the Herald Tribune that day could

have known that while the paper was assigning its two investigative reporters

to Washington and Dallas, the White House and the FBI had already closed the

case. One more time--they closed the

case on the day the President was buried..

We knew nothing about a top-level, secret pact to close the case

prematurely, and that surely was true in newsrooms all over I spent 11 days in Dallas following the

murder of President Kennedy, from November 26 to December 6, and I never

wrote a word about my time there, mostly because I came home with no proof of

anything conclusive about the unanswered questions-- many of which are still

unanswered I came home only with a

deep, unsettling feeling that I was leaving Dallas too soon. But as the years go by, I believe I have

an obligation to write some things that I feel strongly about, especially as

November 22 approaches each year.

Every year since 1963, I’ve

been left with (a) major grievances against the highest-ranking people in our

own government and (b) a haunting memory of a private interview with a doctor

who attended the dying President, and (c) some bits and pieces of information

that might help historians to a

consensus on what was most likely the case.

The official finding that Oswald acted alone is believed by almost no

one today.

AT LAST A THOROUGH, HONEST INVESTIGATION The Warren Commission, guided by §

“The

Federal Bureau of Investigation failed to investigate adequately the possibility

of a conspiracy to assassinate the President.” §

“With

an acute awareness of the significance of its finding, the committee

concluded that the FBI’s investigation of whether there had been a conspiracy

in President Kennedy’s assassination was seriously flawed.” §

“The

former Assistant Director, since deceased, who coordinated the FBI’s

investigation characterized the effort in testimony before the Senate Select

Committee with Respect to Intelligence Activities as rushed, chaotic and

shallow, despite the enormity of paperwork that was generated.” §

“The

committee concluded that the FBI’s investigation into a conspiracy was

deficient in the areas most worthy of suspicion--organized crime, pro- and

anti-Castro Cubans, and the possible association of individuals from these

areas with Lee Harvey Oswald and Jack Ruby.

In those areas in particular, the committee found that the FBI’s

investigation was in all likelihood insufficient to have uncovered a

conspiracy.” §

“The

committee established that the FBI’s own Organized Crime and Mafia

specialists were not consulted or asked to participate to any significant

degree. The Assistant Director who was

in charge of the Organized Crime division--the Special Investigations Division--told

the House committee, ‘They sure didn’t come to me…We had no part in that that

I can recall.’” §

“The

committee further concluded that the critical early period of the FBI’s

investigation was conducted in an atmosphere of considerable haste and

pressure from Final reports from Congressional committees

don’t get any tougher than that.

Especially as they relate to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Beginning in late 1977, the House committee

pieced together Jack Ruby’s connections to organized crime, something the FBI

had brushed off and the Warren Commission simply ignored. Incidentally, Chief Justice Earl Warren

made a critical error at the outset of his assignment. He decided the Warren Commission did not

need investigators. He assembled a

staff of 14 lawyers and relied almost exclusively on the FBI for the

investigative work. He and his

Commission did this with full knowledge the FBI had already given them a

hastily prepared report—written before they even began-- that found no

evidence of a conspiracy. The investigation by the

House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) was directed by G. Robert

Blakey, whose first job in As

chief counsel to the McClellan Committee, Kennedy relentlessly pursued both

Jimmy Hoffa and Paul Dorfman, and the sweetheart deal they had reached. Dorfman gave Hoffa the Mob Muscle he needed

to consolidate his growing power in the Teamster hierarchy, and in return

Dorfman’s stepson Allen was given control of investments by the massive

pension funds of the Central States Conference of Teamsters. The Dorfmans, father and stepson, made

millions on the arrangement, and to this day no one knows how much of that

money was shared with their partners in crime. Paul Dorfman, remember, ran the Teamster

leader James R. Hoffa despised Bob Kennedy, which was well known at the

time. Hoffa also hated John F.

Kennedy, who sat in on the McClellan Committee hearings as a Senator from “In the most remarkable of all my exchanges

with Jimmy Hoffa,” Kennedy wrote, “not a word was said. I called it ‘the look.’ It was to occur fairly often, but the first

time I observed it was on the last day of the 1957 hearings. During the afternoon I noticed that he was

glaring at me across the counsel table with a deep, strange, penetrating

expression of intense hatred. I

suppose it must have dawned on him about that time that he was going to be a

subject of a continuing probe—that we were not playing games. It was the look of a man obsessed by his

enmity, and it came particularly from his eyes. There were times when his face seemed

completely transfixed with this stare of absolute evilness. It might last for five minutes—as if he

thought that by staring long enough and hard enough he could destroy me. Sometimes he seemed to be concentrating so

hard that I had to smile, and occasionally I would speak of it to an

assistant counsel sitting behind me.

It must have been obvious to him that we were discussing it, but his

expression would not change by a flicker. “During the 1958 hearings, from time to

time, he directed the same shriveling look at my brother. And now and then, after a protracted,

particularly evil glower, he did a most peculiar thing: he would wink at me. I can’t explain it. Maybe a psychiatrist would recognize the

symptoms.” Now

in 1963, several years after he experienced and then wrote those words, Bob

Kennedy was burying his brother, but across On the plane from Consider

the blizzard of long-distance telephone calls unleashed by Ruby in the three

weeks prior to the assassination.

Blakey and his House Committee found a Suspicious?

How about stunningly suspicious?

Many of Ruby’s frenetic phone calls were to associates of Organized

Crime chieftains Santo Trafficante and Carlos Marcello, and ultimately to a

very close associate of Jimmy Hoffa--two such calls in November were to

Robert “Barney” Baker, Hoffa’s notorious strong-arm man for many years. At one point in testimony before the HSCA,

Baker said there was “nobody closer to Jimmy Hoffa” than himself. Baker was a 320-pound gorilla whose dearest

friends were ruthless killers. He

appeared before the McClellan Committee in 1958 and an exchange with Chief

Counsel Robert Kennedy says all you need to know about Barney Baker. He was asked about the killing of Anthony

Hintz, a famous District Attorney Hogan was later on

top of a gangland attempt by Hoffa to gain control of the Mr. Kennedy: Do you know Cockeye Dunn? Mr. Baker: I don’t know him as Cockeye

Dunn. I knew him as John Dunn. Mr. Kennedy: Where is he now? Mr. Baker: He has met his maker. Mr. Kennedy: How did he do that? Mr. Baker: I believe through electrocution in

the City of Mr. Kennedy: Did you know “Squint” Mr. Baker: Mr. Sheridan, sir? He also has met his maker. Mr. Kennedy: How did he die? Mr. Baker: With Mr. John Dunn. Mr. Kennedy: He was electrocuted? Mr. Baker: Yes, sir. Mr. Kennedy: He was also a friend of yours? Mr. Baker: Yes, he was a friend of mine. Chief Counsel Kennedy then asked Baker

about a third man involved in the killing of Anthony Hintz, a gangster named

Danny Gentile. Mr. Kennedy: Where is he now? Mr. Baker: I don’t know where he could be

now—excuse me. I believe he was

implicated in a certain case in Mr. Kennedy: That was the Hintz killing. You see we have testimony that you were

closely associated with these people, Mr. Baker. Mr. Baker: Yes, I knew them real well. For good measure, Baker testified he knew a

number of other underworld luminaries, such as Joe Adonis, Meyer Lansky,

Bugsy Siegel, Trigger Mike Coppola and Vincent Alo, (also known as Jimmy Blue

Eyes) who was identified as a close friend of Cockeye Dunn at the trial. Ten years or so after the Hintz murder,

when I was a young reporter at the Journal-American, a veteran NYPD detective

told me Vincent Alo was the new Boss of Bosses in Hoffa

took the witness stand immediately following Baker’s appearance, and after

saying Barney Baker “works under my direct orders,” Hoffa was asked if Baker’s

testimony that he associated with killers, gangsters, gamblers, racketeers,

traffickers in narcotics and human flesh bothered him at all. The response

was typical Jimmy Hoffa. “I am sure, hearing him testify here

that he knew every one of them…it doesn’t disturb me one iota.” I’m

focusing on Jack Ruby’s phone calls to Barney Baker shortly before the

assassination of President Kennedy (two of dozens of such calls Ruby made to

known racketeer enemies of the Kennedy brothers) because those lengthy

conversations between Baker and Ruby two weeks before the President was

murdered should have set off loud alarms in law enforcement circles

immediately. For

emphasis--Immediately. Repeat--Right

Now, Stupid. Barney

Baker called Jack Ruby from Baker was under oath, but he had a comfort

level against a possible perjury charge--when he was interviewed by the HSCA

in 1978 Ruby had been dead for 1l years.

But that brings us to how the Warren Commission handled the same

telephone log information 14 years earlier, when Ruby was in custody and

still alive. Baker wasn’t interviewed

by the FBI until Another of the suspicious phone calls was to

Irwin Weiner, a notorious money man for the Teamsters and the Mob. Weiner wrote bonds for huge loans from the

Central States Conference of Teamsters (Hoffa) to mob-connections in So

when he testified at the HSCA many years after the phone call, Weiner adopted

the same line Barney Baker used--he testified Ruby called to ask him to write

a bond that Ruby needed to bring an injunction against the American Guild of

Variety Artists, and Weiner told him he didn’t want to get involved in a

Texas matter, far from his Chicago office.

That alibi was so unbelievable that Members of the Congress on the

committee took turns telling Weiner they didn’t believe him. Were there no insurance agencies in |

||||

|

Robert F. Kennedy |

J. Edgar Hoover |

|||

|

ATTORNEY GENERAL ROBERT KENNEDY EXCLUDED When

President Johnson and FBI Director Hoover agreed on the appointment of the

Warren Commission and immediately provided the fledgling committee with an

FBI report that said there was no conspiracy to kill President Kennedy,

Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy and the Justice Department were cut out of

the loop. The FBI works for the

Attorney General, but in this case President Johnson decreed that It wasn’t just Barney Baker and Irwin

Weiner. Many of Ruby’s toll calls were

placed to associates of two major Organized Crime chieftains that controlled

the South and Southwest--Santo Trafficante of By

1964 that initial list of 40 had grown to 2,300 Organized Crime figures and

175,000 profiles in the Justice Department’s master file on Carlos Marcello had another, more personal

reason to want either or both of the Kennedy brothers dead. On Eventually the two wanderers made contact

with Guatemalan officials again and this time things went a little more

smoothly. Actually, this time they got

the red carpet treatment. Marcello and

his lawyer were flown on a Guatemala Air Force plane to “Two marshals put the handcuffs on me and

they told me I was being kidnapped and being brought to Guatemala….and in

thirty minutes…I was in the plane…They dumped me off in Guatemala…They just

snatched me, and that is it, actually kidnapped me!” Writing in his book Fatal Hour,

Chief Counsel Blakey said Marcello explicitly fixed the responsibility for

his deportation: “(Kennedy) said…he

would see that I be deported just as soon as he got in office. Well he got in office January 20…and April

the 4th he deported me.” Attorney General Robert Kennedy was just

getting warmed up when his marshals flew Marcello out of the country. Six days later the Internal Revenue Service

filed an $835,000 tax lien against Mr. and Mrs. Marcello, and less than a

week after he returned to the Arthur Schlesinger Jr. was a trusted friend

of the Kennedy family, and on the night of “There could be no serious doubt that

Oswald was guilty,” Kennedy replied.

“But there was still argument if he had done it by himself or as part

of a larger plot, whether organized by Castro or gangsters.” That conversation was less than three weeks

after the assassination, and if at that moment Bob Kennedy knew Jack Ruby had

telephone contacts with Barney Baker

and Weiner and associates of Trafficante and Marcello in the weeks before his

brother was murdered, that almost certainly would have spurred the Attorney

General into action of some sort Bob

Kennedy knew Baker from personal experience and his band of brothers at the

Justice Department knew all of the gangland players identified years later by

the House Select Committee. If they

knew Jimmy Hoffa’s closest associates were in Jack Ruby’s November telephone

records, along with known associates of Trafficante and Marcello, Robert

Kennedy and his Justice Department could not have remained silent. Which raises another question that is so

difficult to comprehend. How could all

of that talent and knowledge and experience at Attorney General Robert

Kennedy’s Justice Department have been silenced for the 10 months the Warren

Commission conducted its inquiry?

Initially, Bob Kennedy removed himself from the events that followed

the assassination of his brother, on the grounds that it would not seem

proper for him to lead the investigation.

But he and his powerful Organized Crime strike force accepted the role

of unconcerned spectators totally. At

no time from the murder in SPINNING MY WHEELS IN When

the FBI quickly leaked its conclusions that Oswald acted alone and Ruby

killed Oswald to avenge the murder of the President, much of the air went out

of my Agronsky’s interview remains a classic

instruction for young journalism aspirants everywhere. Always sensitive, always conscious of the

Governor’s condition and his wife’s concerns, always aware that the Governor

and his wife were wounded witnesses to history, Agronsky’s interview nevertheless

documented the horrifying moments in the rear seats of an open limousine in

Dallas that can never be fully explained or forgotten. Agronsky and the reporters downstairs

hanging on every word by Governor Connally, had no idea that the Governor’s

recollections of what happened that day would conflict with the conclusions

of the Warren Commission a year later.

Somehow, Governor Connally’s most critical moments meant nothing at

all to the Warren Commission. His

recollections didn’t fit their findings. I had been elsewhere scrounging for any

scrap of information missed by the first wave of reporters to descend on

Dallas and when I got to Parkland Hospital just in time to learn that the

Agronsky interview would be taking place upstairs, I missed the briefing that

instructed the pool reporters that the TV interview would be embargoed for an

hour to give the reporters assembled downstairs time to file. I alerted my

newsroom and I took only a few sketchy

notes as Agronsky worked his deft touch, believing the interview was going

live around the world and I was covered by my newsroom back in The

interview over, I called my office and said, “Okay. Did you get all that?” “Get all what?” was the answer. “We don’t have anything.” Oh, no.

My first solid story down there, and all I had was sketchy notes. A I felt like a dope, but the paper put my

byline on the story and nobody gave me any more grief than I had already

taken upon myself. After that incident, I told the City Desk

there was too much happening in There were no more glitches, and when

Ferretti arrived a day later I was pretty much free to roam again. In fact, there were occasions when I wanted

Fred to accompany me. One such

memorable evening was an interview with Dr. Malcolm Perry at his home. Dr. Perry was among the team of doctors at The meeting with Dr. Perry occurred the

evening of December 2. Fred and I were

joined by Stan Redding, a first-class crime reporter for the Houston

Chronicle. I’d taken a liking to Our meeting with Dr. Perry was after

dinnertime at his home, and I remember a little girl playing with her toys on

the living room floor as the three reporters and her father talked about how

he tried to save a President’s life.

She was oblivious to the gravity of the conversation, playing quietly

with her toys throughout. Dr.

Perry had become a controversial figure in the assassination story--to his

dismay. With the President lying on

his back on a gurney, fighting for breath in his dying moments, Dr. Perry

tried to create an air passage with an incision across what he believed to be

an entrance wound at the front of Kennedy’s neck. The President was pronounced dead soon

after, but the doctor’s incision at the throat had forever foreclosed a

conclusion that the wound was an entrance wound or an exit wound. Late that Friday afternoon, the So

little more than a week later, three reporters were speaking quietly to the

surgeon at the center of the dispute.

As far as I know, it was the first and only such private interview

with Dr. Perry. None of us in his

living room that night took out a notebook or a pencil. It was a conversation with a clearly

reluctant surgeon who had done his best in a crisis and who had agonized

about it since. Dr. Perry said he believed it was an

entrance wound because the small circular hole was clean, with no edges. In the course of the conversation, he was

asked and answered that he had treated hundreds of gunshot victims in the

Emergency Rooms at But he told us that throughout that night,

he received a series of phone calls to his home from irate doctors at the When

he was finished, there was only one question left. I asked him if he still believed it was an

entrance wound. The question hung

there for a long moment. “Yes,” he said. Ultimately

Dr. Perry appeared as a witness before the Warren Commission. In substance he testified that he realized

he had no proof the bullet hole in the President’s neck was an entrance

wound, and he conceded that the I can’t fault Dr. Perry for his testimony

before the Warren Commission. Surely

it occurred to him there was no point in holding out for a belief that

couldn’t be proved. And just as

surely, this 34-year-old surgeon with an exemplary record and a brilliant

future knew his life would be forever shadowed by conspiracy theories that

relied heavily on a bullet fired from the front. He testified only as he most certainly had

to testify. But I’ll never forget what

he said to three reporters that night in The

interview in Dr. Perry’s living room was the most memorable moment, but there

were other disturbing bits and pieces of information from my time in OSWALD AND THE POLICE OFFICER HE MURDERED Oswald shot the President and he dropped his

rifle and beat it out of the School Book Depository building. He got on a bus to his rented room in a A police car driven by Officer J. D. Tippett

pulled alongside Oswald and Tippett told him to stop right there. The police radios had been crackling with

alerts about a lone gunman since the firing on the Presidential

motorcade. The officer got out and was

headed around the front of his car to question Oswald, who pulled his pistol

and fired several shots across the hood of the car, killing Officer Tippett

instantly. Oswald turned and ran back

toward But

where was Oswald going on foot when Officer Tippett pulled alongside and

stopped him? Where was the killer

going on foot? He had to be going

somewhere, and on foot. That question

is rarely asked and has never been answered.

He wasn’t going to the When Fred Ferretti arrived to join me, I

thought it might be worthwhile to return to Oak Cliff and pick up Oswald’s

walk from where he was stopped by Officer Tippett, and on to where Ruby

lived. Maybe I missed something the

first time, something we might get with another try. Maybe Fred and I would find someone who

knew something of interest, but it was another failed effort and we

didn’t. We did go somewhat further

than I had on the first trip though.

Behind the garden apartment complex where Ruby lived was a major The

House Select Committee on Assassinations turned up some fascinating

coincidences that, taken together, prove nothing except As I said before, I never wrote anything

about my time in Many years later the House Select Committee

on Assassinations was able to gain access to some of J. Edgar Hoover’s personal

files for those days immediately following the murder of President

Kennedy. Here are a few revealing

segments: My own assignment in “Who

is the high- ranking person in the Justice Department who gave the AP that

story?” I asked “J. Edgar Hoover,” he said. “How do we know?” “Our Washington Bureau says so.” “Well, I guess there isn’t going to

be an FBI roundup of conspirators,” I said. “Doesn’t look like it,” Buddy

said. “How much longer are you going

to be down there? Fred can handle it

if you think you should come home.” “I have a couple of things still

bothering me. Give me a couple more

days.” “Okay, but if you think you’re

spinning your wheels down there, pack it in and come back.” I’ve often wondered how many more reporters

were ordered home from |

||||