|

By Patrick Fenton

“That’s

right. That’s right, Neal kept saying and all the time he was only concerned

with locking the trunk and putting the proper things in the compartment and

sweeping the floor and getting all ready for the purity of the road again,

the purity of moving and getting somewhere, no matter where, and as fast as

possible. We roared off. Neal pushed the Hudson through the Lincoln Tunnel and we were in New Jersey. It was drizzling and mysterious at the

beginning of our voyage. I could see that it was going to be one big saga of

the mist. ‘Here we go! ‘yelled Neal. And he gunned

her.”

(Jack Kerouac. “On the Road.”)

For a long time the original

manuscript that those words were written on remained in an old vault in

Kerouac’s agent’s office, Sterling Lord. In the 80’s his books weren’t

selling that well, and for awhile it looked like his time had come and gone.

The manuscript of “On the Road” was a large, cumbersome, scroll that took up

room. No one in the book publishing industry had ever seen anything like it

before. It was 120 feet long, one long paragraph written on tracing paper

taped together by Jack Kerouac so that he could feed it into his typewriter.

It’s a wonder that over the years it remained in the safe, that no one had

ever thrown it out.

In

November, this original manuscript of “On the Road,“ the actual 120 foot

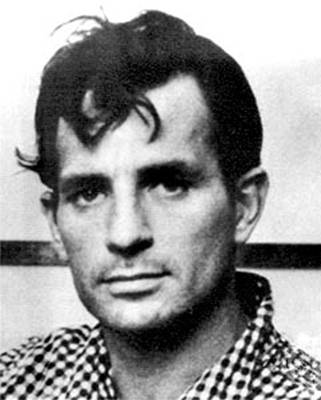

scroll, will be on exhibit at the New York Public Library. Jack

Kerouac died on October 21, 1969, 47 years old, broke. Then after his death, there

was a long, dry period where little was written about him. His estate was

worth just a few hundred bucks, if that, and his

books stopped selling. Then, like a dam breaking, it seemed that every other

year a new biography would be out about him.

On May 22, 2001, the scroll was auctioned off at Christie’s in New York City. Jim Irsay, the owner of the Indianapolis Colts

bought it for almost two and a half million dollars. There have been volumes

of books and essays written on Jack Kerouac, but still, after a long period

he has remained one of the most misunderstood, underrated writers of our

time. Surprisingly, with all the attention paid to him, a definitive

biography of his life still hasn’t been written.

And now, on the 50th Anniversary of the publication of “On the

Road,” “the writers and critics who prophesize with their pens” are back

taking another shot at him, even though the book has been published in 32

languages and sells 100,000 copies a year according to its publisher, Viking

Penguin. Recently they released a 50th anniversary edition of it

along with the manuscript of the original scroll that he wrote it on,

published in book form for the first time, and a companion book, titled “Why

Kerouac Matters” by New York Times reporter, John LeLand.

In the beginning, there

were only a few who recognized Kerouac’s great literary talent as an American

novelist. Gilbert Milstein of the New York Times was the first when in his

review of the book he said, “there are sections of ‘On the Road’ in which the

writing is of a beauty almost breathtaking.“

After that one review in the New York Times in 1957, fame came to him

overnight. But he wasn’t comfortable with it. He was lost somewhere between

the innocence of those first promising, early days when he signed his books

“John Kerouac”, and the awful hurt that comes so often with literary success

in America.

He tried to hide out in the suburbs of Northport, Long Island, drinking his fill of whiskey and beer every

night with the local clam diggers who hung out in Peter Gunther’s Bar on Main Street. They say when winter came to that harbor town;

you would always find him hunched over a table at the back of the bar next to

the warmth of a kerosene heater. Eventually, in the fall of 1964 he fled even

further, down to St.

Petersburg Florida with his aging mother who always took care of

him.

For a while, he tried to go home again to his hometown, Lowell Massachusetts, and then eventually he headed back South to St. Petersburg. Then on February 3, 1968, his protagonist for “On the Road”, Neal

Cassady, his old road buddy, died. Before his death, which happened along the

railroad tracks after an afternoon of drinking at a wedding in San Miguel, Mexico, he had started telling friends that he was

tired of being Keroassady.

After that, Jack Kerouac spent most of his days and nights drinking whiskey

out of an aspirin bottle and recording his own voice as he talked to a black

and white television with the sound off. The few times that he made it into

town by cab, he was beaten badly in bar fights. Some nights he would be

dragged through the crowd by his pants belt by one of the bar regulars who

recognized him. And they would yell over the din of Saturday night bar band

music — listen up — listen up — this here guy is Jack Kerouac, the guy who

wrote “On the Road.” By then he was so red faced and fat, his belly bulging

out from a hernia, which he held in place with a silver dollar, nobody would

believe him. And as old John Mellencamp might say, “ain’t that America.“

Even now, as America and the World

celebrates the 50th anniversary of the writing of this American

classic, there are still some naysayers who write that “On the Road” is an

outdated book that the present generation of young people find little to

identify with.

But they are wrong. The very core of “On the Road” is in its beautiful,

sensitive descriptions of America, and the idea that once you could get lost in

its vastness for a while as you were growing up. The actor, Nick Nolte, once

said that after reading “On The Road“ in high school

in Omaha, “I remember thinking, ‘you can just do that?

Pick up and go?’ It seemed incredible to me.’”

In this world of Google and text messaging, I’m not too sure that is possible

anymore, even if young people are willing to get up from their computer

screens for a while and get on a Greyhound, or behind the wheel of a car.

That is what makes “On the Road “important. It once happened in America.

The one biographer

who always understood this is the noted historian Douglas Brinkley, the

author of “Jack Kerouac, Windblown World,” a collection of his journals. He

understood that Jack Kerouac was writing about America in a way that had not been done before, through the view of a rear view mirror of a car stirring up road

dust as it drove through a sleepy American town at 3 in the morning doing

over 90 mile an hour.

“He

was opening up the West in his writing to a new degree,” Brinkley recently

said during an interview with the Library of America. “Certainly Mark Twain

wrote about the West as did Jack London, Bret Harte, and Frank Norris. It

wasn’t new terrain but Kerouac brought modernity to it. He brought the

automobile into the West as a kind of spiritual playground where you can

travel at whim and find freedom. If you got a tank of gas you could go

anywhere in any direction at any time.”

Listen

for a moment to the ghosts of old Sal Paradise, and Dean Moriarty; still out

there somewhere in a lost America.

“’Well yes, well yes, and now I think we better be cutting along because we

gotta be in Chicago by tomorrow night and we already wasted several hours’….

I turned to watch the kitchen light recede in the sea of night. Then I leaned

ahead. In no time at all we were back on the highway and that night I saw the

entire state of Nebraska unroll perceptibly before my eyes. A hundred and

ten miles an hour straight through, an arrow road, sleeping towns, no

traffic, and the Union Pacific streamliner falling behind us in the

moonlight. …All the Nebraska towns — Ogallala, Gothenburg, Kearny, Grand Island, Columbus — unreeled with dreamlike rapidity as

we roared ahead and talked. It was a magnificent car,

it could hold the road like a boat holds water. Gradual curves were its

singing ease. …’What a dreamboat,’ sighed Neal. ’Do

you know there’s a road that goes down to Mexico and all the way to Panama? — and maybe all the

way to the bottom of South

America…Yes! You and I,

Jack, we’d dig the whole world with a car like this because man the road must

eventually lead to the whole world.”

(Jack Kerouac. “On the Road”)

Ain’t

that America.

table

of contents

|