|

On the Heroin Trail: In Pursuit of the Elusive Kingpin By Les Payne |

|

|

The Hunter: Les Payne |

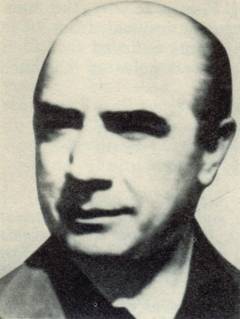

The prey: Corsican-born Marcel

Francisci, France's top-ranking heroin racketeer of the 1970's. |

|

By Les Payne The reporting assignment

was simple enough: go to Corsica and nail Marcel Francisci – the heroin

kingpin of Europe. The smooth criminal had gone respectable, with associates

high in government, and a lethal network dominating drugs moving through the

“French Connection.” During the early ‘70’s,

Francisci and other Corsican mobsters supplied some 80 percent of the heroin

the underworld pushed in the U.S.

Narcotics were corrupting urban police and politicians profiteering

from the street epidemic wreaking crime, social devastation and death. Some

1,100 residents in New York City, chiefly African Americans, died of

heroin-connected causes in ‘72, with another 48 suburban “junkies” succumbing

on Long Island. Our three-man Newsday

investigative team started with the poppy farmers of Turkey, traced the

smuggling routes across Europe, and then zeroed in on the French underworld

running the heroin “labs.” Among the dozens of “contrabandeurs” we

identified, all reports from Interpol and the Bureau of Narcotics and

Dangerous Drugs pointed to one dominant figure. “Marcel Francisci leaves

the actual [heroin] work to other people,” one top U.S. narcotics agent told

us. “He is the financier, the arranger, the fixer. He is the man behind the

desk far away. That why it’s so hard to get at him." His international gambling holdings

included swank clubs in London, ritzy casino in Beirut and the Cerce Housman

in Paris. U.S. officials had

warned us off reporting about Francisci on his home island. The Corsicans,

not unlike Sicilians, are wary of outsiders. Centuries of invasions have

forged the rugged islanders with a fierce pride and a nasty suspicion of

strangers inquiring about any Corsican. Indeed, Francisci was a local hero,

an elected official, a highly decorated WWII veteran and a generous

benefactor who had improved street lighting and roads and built schools and

clinics on the poverty-stricken island.

When our team leader Bob

Greene told Paul Knight, at his Paris office, about our plans to profile the

heroin kingpin on his Corsica home island, the high-ranking BNDD official

seemed stunned. “Well I’m glad you’re going to do it, I sure wouldn’t,” said

Knight, whose drug fighting force had never placed an agent on Corsica. “It’s

too damn dangerous.” Our team leader, who had

no intention of going himself, kept Knight’s dire warning away from Knut

Royce and me. A fluent French-speaker, Knut was initially given the Corsica

assignment. When he fell seriously ill and returned to the states – I drew

this short straw. “As soon as the

Corsicans spot you,” a veteran Nice Matin editor told me in Marseilles, “the

word will be out (snapping his fingers) just like that. “Look,” he said,

they’ll know you’re investigating drug smuggling, “they don’t believe in

tourists over there.” In addition to getting details, ambience and background

on Francisci in Ajaccio, I said I would like to report from Bastia as well as

interview Jean Colonna, the shadowy mayor of Pina Canale, about the old days.

“You are absolutely

crazy if you plan to go to Pina Canale,” the editor said. A week earlier he’d

sent a newspaper photographer there to take pictures of a local festival. “It

had nothing to do with drugs or criminals,” he said. “My photographer was met

at the top of a hill and escorted away from the village by a car full of

armed men.” To buttress his point

about the danger, he telephoned a Corsican friend, a reporter in Ajaccio.

Informed of my reporting plans, the journalist said, “I won’t get involved; I

won’t be responsible,” and hung up. “The Corsicans have what

they call a ‘pinsute,’ that’s someone who is not from the island,” my editor

friend said in grave tones. “They just don’t talk to ‘pinsutes,’ besides,

they’re not too talkative, the Corsicans.” I found three islanders,

one a dissident official, who’d promised to talk to me upon my arrival in

Ajaccio. A mostly young, noontime

crowd flowed past the small, Royal Bar, the former drinking spot of Ange

Simonpieri, a wealthy mobster serving a prison sentence for narcotics

trafficking. As I sipped pastis with the translator, waiting for my first

contact, a woman was carried limp out of the bar by two men who bundled her

into the back seat of a station wagon and drove away. As the crowd returned

to a buzz, the number of young men with bandaged hands and arms, some with

raw tissue exposed, gave the street scene a touch of exotic menace. At 12:30 my source, one

Marchetti, his wavy hair parted in the middle and combed over his ears, gave

a nod and joined us at the table. Over

lunch at an upstairs cafe, we were joined by a local, Corsican journalist who

published a twice monthly newspaper. I told them about my reporting plans for

the four-day trip. “Be very, very careful

around here when you discuss him,” Marchetti said. “This is Francisci

country; he is home when he comes here.” The two Corsicans fell silent each

time the waiter mounted the stairs. “No one can be trusted to overhear

discussions about Francisci and mobsters,” he said. Whereupon, we took a

brief walk outside and created a nom de plume. I agreed not to use

“Francisci” on the island ever again. I gave Marchetti a list

of my interests – Jean-Baptiste Croce’s holdings in Bastia, Colonna’s in Pina

Canale, all there was to know about Francisci. We adjourned, and regrouped at

the Royal Bar at 7pm. The two Corsicans brought along a “young law student

from a very prominent family here in Ajaccio.” Over dinner, the

“student,” asked a series of probing questions. Sensing my hosts extreme

nervousness, I claimed to be a tourist and lied at every other question as

well. The newspaperman coded that he couldn’t discuss matters under the

present conditions and excused himself. The “student” stayed to the end. The next morning, at

11am, I sat on a park bench diagonally across from the Grand Bar. Francisci’s

gang had shot it out with that of a rival there, three years earlier. The

“gambling war” saw 6 mobsters injured and one killed. Francisci’s men

prevailed to control the bar where he held forth when he visited Ajaccio. As I raised my Minox

camera to sneak a picture of this Francisci landmark for our “Heroin Trail”

files, a lean man dressed in black, standing spread-eagle, trained a Bolex-type,

motion-picture camera on us. “Hey Chris,” I whispered, “that guy’s filming us

taking picture of them.” Not quite ready for my close-up on Francisci’s mob

channel, we walked away, slowly at first. When two men from the

Grand Bar ran toward us, we picked up the pace, sprinting down the street and

uphill through a winding alley. A pursuer in a brown jacket and turtleneck

ran into the alley checking doors at the foot of the entryway. Circling the

block, we doubled back to the Fresch Hotel, and dashed to the 6th

floor to pack. One of the men conferred

with the desk clerk and positioned himself in a doorway across the street.

After she called us a taxi for the airport, I blocked the desk clerk’s move

toward the door to confer with the man across the street. Dashing to the cab,

we ordered him to speed for our late plane on the tarmac. Our two

pursuers,organized transportation, and arrived at the airport just as we were

heading up the ramp of the last plane off the island. It was a sweet flight

back to Marseilles. Officials later

speculated that a confrontation with Francisci’s men had been imminent.

Neither police nor any other Corsican would have assisted an American

journalist investigating their island’s hero – and the world’s top heroin

smuggler. On Jan. 16, 1982,

Francisci, described on wire reports as “masterminding the ‘French Connection

drug network,” was shot dead as he was getting out of his car in Paris.

|

|